What do default organ donation, “poll ashtrays” and words of encouragement on long staircases all have in common? The answer is they are all nudges; they gently steer our behavior for our personal benefit. Can nudges be applied to learning to prompt people to learn better? For the best possible analysis of the contribution nudges make to learning, we invite you to read a two-part study:

- the first article defines nudging and provides an overview of research on its applications in education;

- the second article sets out the potential applications of nudges in digital learning.

Nudging? What’s that about?

Nudging was popularized by Thaler and Sunstein’s 2008 best-seller. Located at the crossroads of economics and behavioral psychology, the principle of this technique is to influence our behavior for our own benefit. The concept relies on the fact that individuals have limited rationality and behavioral biases, which prevent them from making the best decisions (individually and collectively). With nudges, the idea is therefore to “play” with these behavioral biases to prompt better decision-making.

Practically-speaking:

- We subtly change the decision environment in order to guide or facilitate “right” decision-making.

- Without changing the material incentives or coercing people.

Concrete examples per scope of application

Nudges are a new and efficient tool which are inexpensive and publicly accepted; the scopes of application are therefore numerous:

- Ecology – encouraging people to sort their waste, reduce their energy consumption, etc.

- Health – encouraging people to eat more healthily, to do exercise, to get tested/vaccinated, to respect health measures, etc.

- Social & political – encouraging people to vote, reducing discrimination, etc.

- Learning – encouraging learners to become involved and persevere with their training.

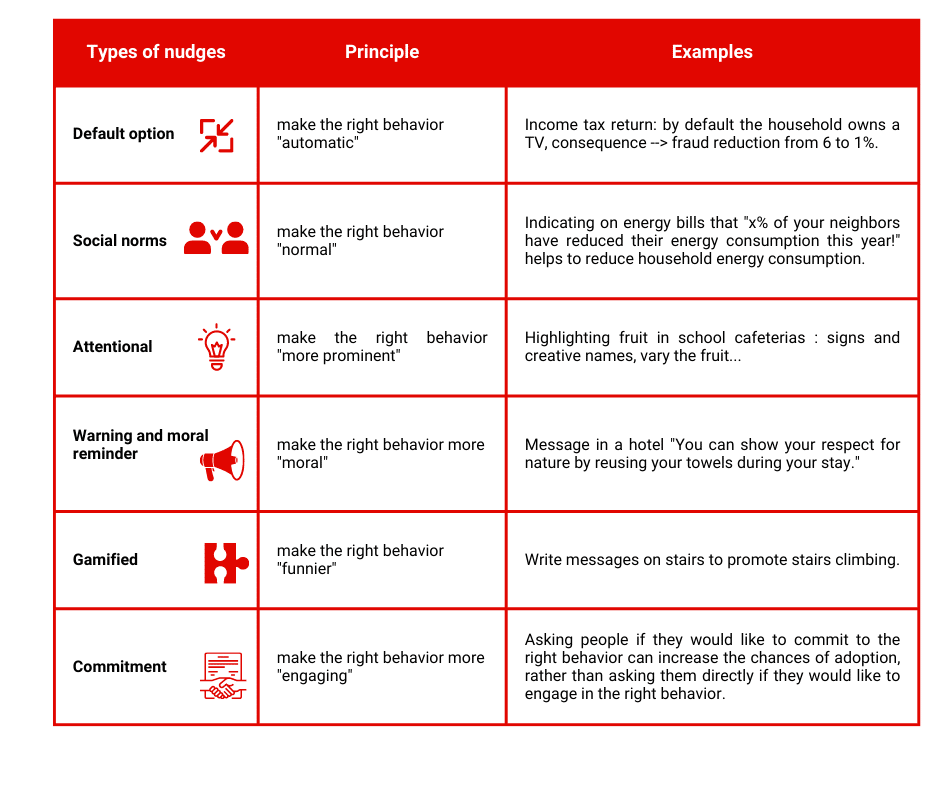

The mechanic of nudges

To fully grasp nudges, here are some practical examples which use differing mechanics, to help us to analyse applications tailored to learning:

Fly sticker inside a urinal at Amsterdam airport – this helped to reduce cleaning costs by 80% in the men’s toilets.

A message stating the number of calories burned per step on a staircase in a Thai school.

A message stating the number of calories burned per step on a staircase in a Thai school.

Nudges in learning

New-found interest

Over the last few years, there has been a proliferation of research into the application of nudges in education. The range of projects is extensive and covers both early childhood and professional training, with a common goal: to encourage virtuous learning without compelling or forcing. The measures involve prompting learners to:

- be more diligent

- persevere

- be ambitious

- respect the rules

- …

Conclusive research

Examples of conclusive research showing the benefits of nudges applied to education:

- A progress monitoring service for children proposed by default to parents: Bergman and Rogers (2017) tested the influence of offering (by default or otherwise) a text message service notifying parents about the performance and diligence of their children (middle school and high school). Only 7.8% of parents made the voluntary decision to accept the service when it wasn’t offered as standard, while 96.5% accepted to adopt the service if it was offered as standard, thereby increasing children’s grades and diligence.

- Allowing students to set their own goals: asking students to set an objective at the start of the year (in terms of endeavours or exam performance) increases the quantity of work, effort and exam results (van Lent et Souverijn, 2017; Clark et al., 2017). These effects are consolidated by the materialization of a commitment and the use of tools helping students to stick to it, (for example enabling students to install blockers for “distracting” sites which they can deactivate when they wish).

- Reminder messages for university enrolment: in the US, to encourage high school students to go on to higher learning, automatic messages were sent to freshly graduated high school students reminding them to enroll for university (with notification of the deadlines and formalities required). This helped to boost the enrolment rate, in particular for students from disadvantaged backgrounds who lack a defined career plan and who receive little help and advice when choosing their studies (Castleman & Page, 2015).

Nudges should be used sparingly!

Nudges should be used sparingly nonetheless, as, in some cases, they bring zero or even counterproductive effects.

Firstly, many studies have resulted in negative effects. Nudges are particularly ineffective when you are trying to modify deeply embedded behaviour or a very conscious, “rational” decision-making process. For example, nudges trying to prompt students to embark on post graduate studies by showing future financial benefits have proven ineffective in developed countries, but have had positive effects in some developing countries, especially if this information is communicated at a young age.

Moreover, nudges can sometimes have the opposite effect to the intended one. For example, Wagner (2017) tested a non-conventional presentation of a multiple-choice quiz scale, translating it into points lost with regard to the maximum grade, rather than points won with regard to the minimum grade. This presentation increased risk-taking among students during the exam, which helped to improve the results of better students but which, on the contrary, decreased those of struggling students.

Additionally, social comparison nudges (for example publicly disclosing the grades of students or comparing students’ grades with regard to an average or to a grade) must be done sparingly as social comparison can, in some cases:

- damage the results of higher achievers (who minimize their efforts in order to move closer to the norm)

- damage the results of lower achievers, who may be discouraged by too high a standard, which they consider unrealistic.

Therefore, recent results suggest that it is preferable to disclose information about the behavior of others (effort made) rather than their performance.

Efficient nudges

Overall, the nudges which obtain the most positive results are those which revolve around identity and social allegiance. These nudges aim to boost learners’ trust in their own abilities in order to put them at ease.

- Reassure learners at the start of the course through grades: Wilson and Linville (1982) notified first year university students that, in general, their grades would increase over the following years. This information slashed first year dropout rates and increased students’ grades.

- Reassure learners at the start of the course by sharing profiles: Walton and Cohen (2011) described the profiles of students having had problems in the first year to newly arrived students, explaining that many did well later on. This kind of nudge, promoting positivity among students, is particularly effective for disadvantaged and minority students.

Now that you know all there is to know about nudging, take a look at the next article which focuses on the use of nudges in digital learning.

D’abord éditrice de manuels scolaires, professeure et coordinatrice pédagogique à l’Université, Julia a rejoint l’équipe Learning Experience chez Teach on Mars pour apporter ses compétences en pédagogie. La gamification et la différenciation pédagogique sont notamment ses chevaux de bataille.